Opioids 101

History and Terminology — Part 3

The Politics of Drug Laws

By knowing what has happened in the past, you can be aware of what might happen again in the future. Laws and regulations often go in cycles. A consistent feature of U.S. laws on drugs is their racist nature. Listen to the current politicians discussing safety and crime control and the debates on drugs; then, think: what do their ideas mean for you and your community? Will more funding for crime control mean more crackdowns in your community and targeting of Black and Brown people? Don’t be a couch potato — find out who is running for election — not just for president but in your local area. Then, get out to vote. The people you elect are the people who will be making laws that will affect you and your family. By voting, you can change the course of history.

Racial Disparity

Black Americans

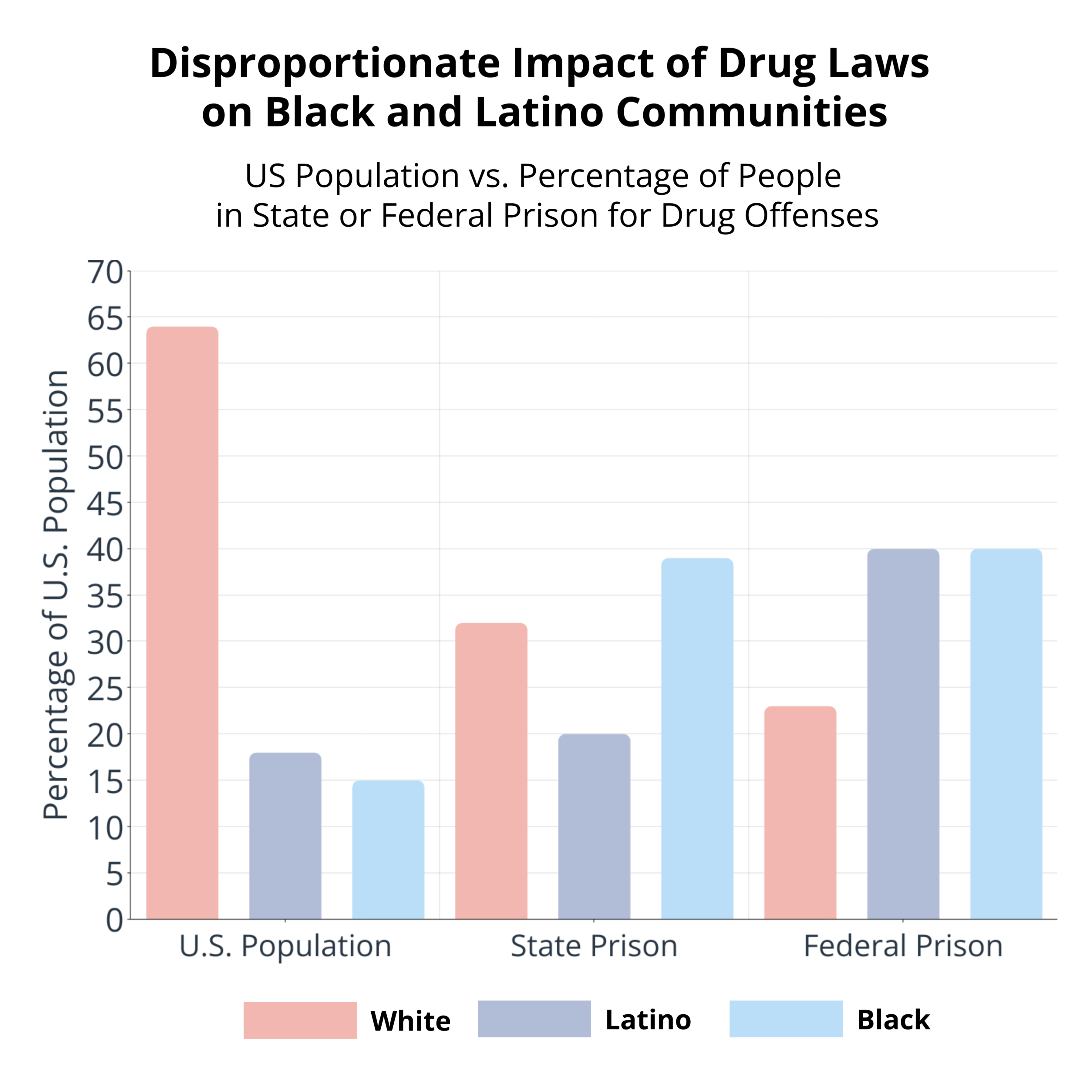

Black Americans use illicit drugs at similar rates as Whites but are six to ten times more likely to be incarcerated for drug offenses (Bigg, 2007; Goode, n.d.), leading to a higher proportion of Blacks in prison (Nellis, 2023).

Hispanic Americans

As Hispanic/Latinos are one of the fastest growing minority populations— expected to comprise nearly 30 percent of the U.S. population by 2060(5) — it becomes imperative to understand the unique sociocultural factors that influence drug use and access to prevention, treatment, and recovery in this population.

According to the SAMHSA’s National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the opioid misuse (heroin use and prescription opioid misuse) rate among Hispanics/ Latinos is similar to the national population rate, about 4 percent. In 2018, 1.7 million Hispanics/ Latinos and 10.3 million people nationally aged 12 and older were estimated to have engaged in opioid misuse in the past year.

National data from multiple sources specific to high school-aged youth indicate that Hispanic youth are using drugs at rates equivalent or higher compared to their racial/ethnic peers. In 2017, the YRBS reported that high school Hispanic youth had the highest prevalence of select illicit drug use (16.1 percent) and prescription opioid misuse (15.1 percent) compared to the total high school youth population (14.0 percent for both) and other races/ethnicities.

“’Familiso’ is a term used in Hispanic/Latino culture to underscore the importance of the family and family roles. Familismo emphasizes the critical role of internal family dynamics, extended social networks, and the distribution of resources through these networks. This concept is critical to prevention, treatment, and recovery approaches for Hispanic/ Latino communities. In general, SUD treatment interventions based on family system models and the involvement of family members throughout the treatment continuum, from engagement through continuing care have shown success, according to SAMHSA, 2020.

Opium Den Ordinance

Harrison Narcotics Act

Anti-drug Abuse Act

First Step Act

Marijuana Tax Act

Nixon’s War on Drugs

Fair Sentencing Act

Historical Evolution of Drug Laws

1875 — Opium Den Ordinance

The 1875 Opium Den Ordinance was the nation’s first anti-drug law, banning opium dens. The ordinance was directed at Chinese immigrants and led to racial disparities in drug policies and addiction treatment (Mark, 1975)

1920 — Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution in 1910 led to the immigration of Mexicans to the U.S. Southwest. Some immigrants brought marijuana with them. Texas police officers claimed that marijuana aroused a “lust for blood,” leading to violent crimes. In 1914, El Paso, Texas was the first city to ban the sale or possession of marijuana (Schlosser, 1994).

1937 — Marijuana Tax Act

The Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 targeted Mexican Americans, with increased penalties for drug possession.

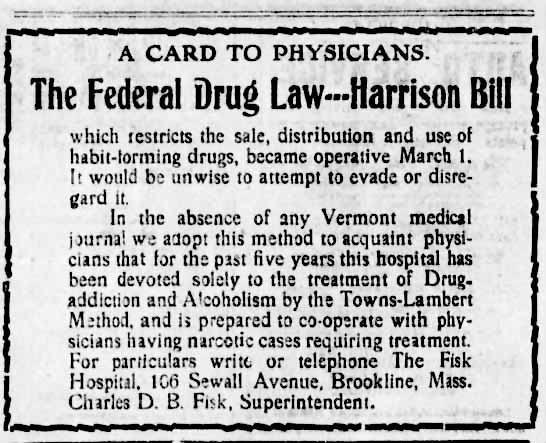

1914 — Harrison Narcotics Act

In 1914, the U.S. Congress passed the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, imposing “a special tax” upon all persons who produce, import, manufacture, compound, deal in, dispense, sell, distribute, or give away opium or coca leaves, their salts, derivatives, or preparations, and for other purposes.” This law banned doctors from prescribing opioid-based drugs, leading to the arrest and imprisonment of many doctors, which led to underground markets of opioids and cocaine and increased police enforcement, according to the Drug Policy Alliance.

What is the Drug War? With Jay‑Z & Molly Crabapple

The Drug Policy Alliance has teamed up with artists Jay-Z and Molly Crabapple to tell the brief history of how the Drug War went from prohibition to the gold rush of the legalized cannabis industry. Do you know your history?

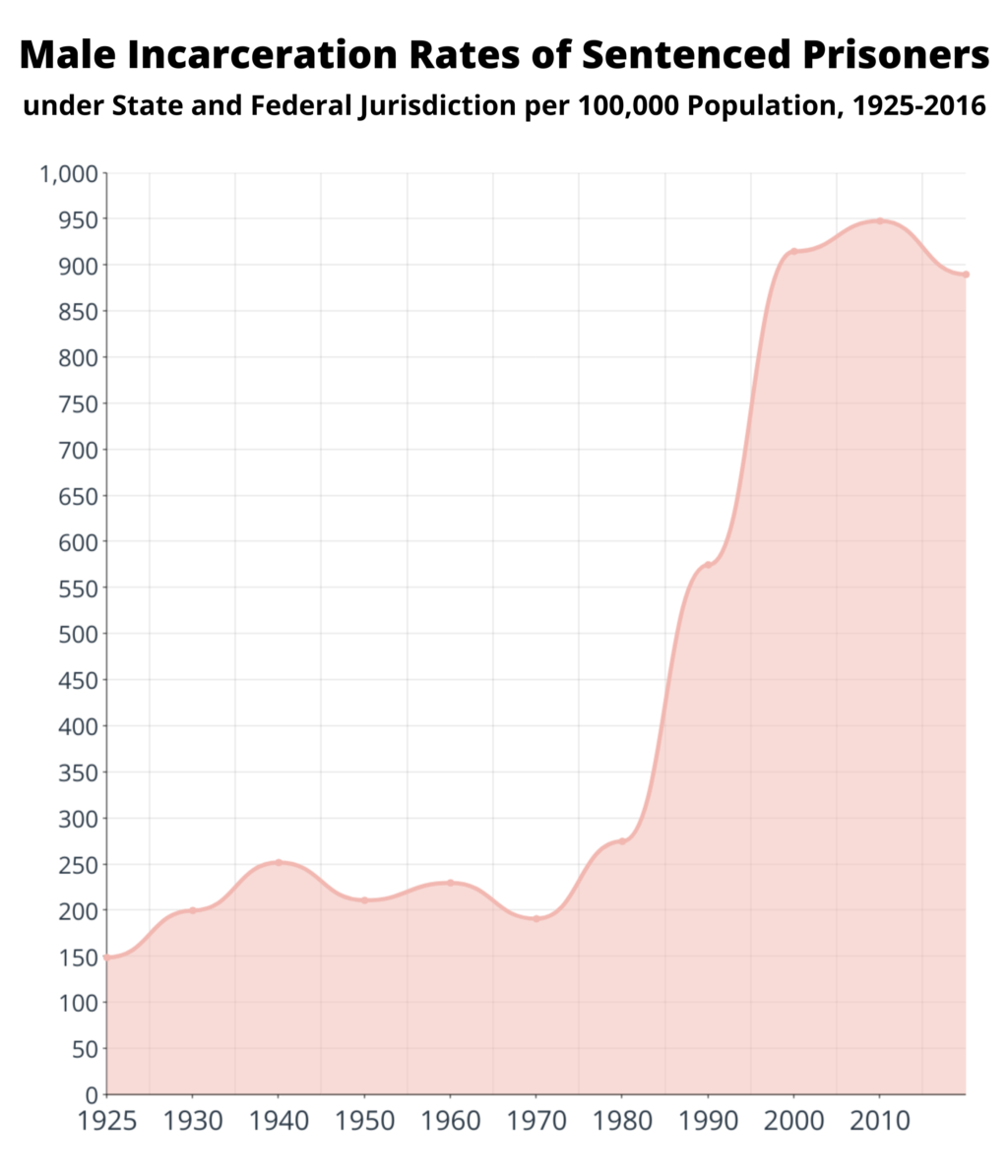

1970 — The Comprehensive Sentencing Act

The Comprehensive Sentencing Act of 1970, signed by Richard Nixon, was a precursor to his declaration of the War on Drugs a year later, which contained punitive sentencing guidelines. The War on Drugs in 1971 reversed mid-century civil rights and Great Society commitments, which focused on social programs to address poverty and, subsequently, crime.

The drug war legislation expanded the scope of criminal justice and culminated in decades-long mass incarceration by:

- Increasing mandatory minimum sentencing

- Using plea bargaining

- Implementing drug raids and asset forfeiture

- Allocating funds for policing and the building of state prisons

- The broadening of state surveillance

1986 — Anti-Drug Abuse Act

Systemic racism in drug policy is also recognizable in the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, “which enacted a 100-fold greater sentencing disparity for water-soluble cocaine base (‘crack’) versus powder cocaine,” according to ASAM’s policy statement.

- The distribution of five grams of crack, mainly used by Black people, carried a minimum of a five-year sentence in federal prison.

- Distributing 500 grams of powder cocaine (mainly used by White people) had the same sentencing.

The law resulted in the arrest of a disproportionate number of Blacks compared to Whites.

- Triggered by the abolition of slavery, many Whites advocated that formerly enslaved people be sent back to Africa or remain under control. Whites’ fear for their safety led them to seek ways to control the Black population. Part of this was through the war on drugs.

- The war on drugs reinforced racial hierarchies through differential enforcement and perception about what constitutes addiction (Netherland & Hansen, 2017). It subjected millions to criminalization, incarceration, and lifelong criminal records, disrupting or eliminating access to adequate resources and support to live healthy lives (Cohen et al., 2022).

- The effects of the war on drugs include the expenses families suffer from the loss of the economic contributions of incarcerated family members and the need for extra help for the children of incarcerated parents (Wagner & Rauby, 2017; Sawyer, & Wagner, 2023). What is more, these children of incarcerated parents are subject to additional risk factors of substance misuse, as seen in the ACEs module.

- Further, in the case of opioids, addiction treatment is being selectively “pharmaceuticalized” to preserve a protected space for White opioid users while leaving intact a punitive system for Black and Brown individuals who use drugs (Netherland & Hansen, 2017).

“The War on Drugs That Wasn’t: Wasted Whiteness, ‘Dirty Doctors,’ and Race in Media Coverage of Prescription Opioid Misuse.”

“The past decade in the U.S. has been marked by a media fascination with the white prescription opioid cum heroin user. In this paper, we contrast media coverage of white non-medical opioid users with that of black and brown heroin users to show how divergent representations lead to different public and policy responses.”

Racism and the War on Drugs

Smith College School for Social Work in Conversation with Leigh-Anne Francis, Ph.D.

“… Most Black folks are locked up every year are for nonviolent low-level drug crimes. Now what is disturbing is that most drug users are White. I mean overwhelmingly most drug users are White, White middle-class youth …”

2010 — Fair Sentencing Act; 2018 First Step Act

In 2010, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act, reducing the sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine to 18 to 1. The amount of powder cocaine triggering a minimum sentencing of five and ten years remained unchanged.

In 2018, the First Step Act was signed into law, making sentencing reforms of the Fair Sentencing Act retroactive, but left out those previously arrested for low-level offenses that involved 0 to 5 grams of crack cocaine.

Test Your Knowledge (answer yes or no)

1. Children of incarcerated parents are often substance users.

YES. Having an incarcerated parent is one of the adverse childhood effects that often leads to substance abuse. Adolescents with incarcerated parents might receive less monitoring from their caregivers while role-modeling the behavior of the incarcerated parent, which can increase the likelihood that adolescents will engage in antisocial behavior such as aggression and substance use, particularly when they are spending time with peers who are engaging in such behaviors.

2. The Drug War began many punitive actions by the government that have continued.

YES. Some of the things that began with the Drug War included legislation expanding the scope of criminal justice and resulting in mass incarceration through increasing mandatory minimum sentencing, the use of plea bargaining, implementation of drug raids and asset forfeiture, greater funding for policing, and the building of state prisons.

3. One of the reasons for the great expansion of incarceration in the United States was caused by drug war legislation, which increased mandatory minimum sentencing.

Yes. According to the Brennan Center on Justice, “Prosecutors’ use of mandatory minimums in over half of all federal cases disproportionately impacts poor people of color and has driven the exponential growth in the federal prison population in recent decades. All 50 states and DC also have mandatory minimum sentencing laws.”

4. Every group is incarcerated for drug offenses at the same rate.

No. Minorities, such as Black people or Hispanic people, are far more likely to be sent to prison for drug offenses, even though White people use drugs at the same rate.

5. Many groups today are fighting to decrease the opioid problem in the United States.

Yes. The North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition (NCHRC) and Opioid Rapid Response Program (ORRP) are just a few examples.